2018 in review

/A year ago today we officially became Causeway Education – introducing our new name to mark becoming a charity and to acknowledge that we do more than just get young people to university.

To mark our birthday, here we take a moment to reflect on everything that's happened this past year.

The year in review

In April we hosted our very first conference, Partnerships for Change, in London, welcoming over 150 friends and colleagues for a busy day's discussion of how organisations can work together to improve outcomes for young people.

Highlights included MoneySavingExpert Martin Lewis' passionate keynote on the state of student finance and the chance to hear perspectives from schools and colleges, voices often missed from the debate about widening participation.

You can read a full wrap-up of the conference, and watch recordings of all the sessions, on our blog.

All year we've been busy in schools and colleges around the country, working with teachers and students to help make sure that all young people have fair access to their best possible future.

We've mentored more than 1,000 students this year, and in June we caught up with Sarah Baylis, one of our Progression Specialists, to see what a day out and about in school is like, when she wrote about her visit to the Isle of Wight on our blog.

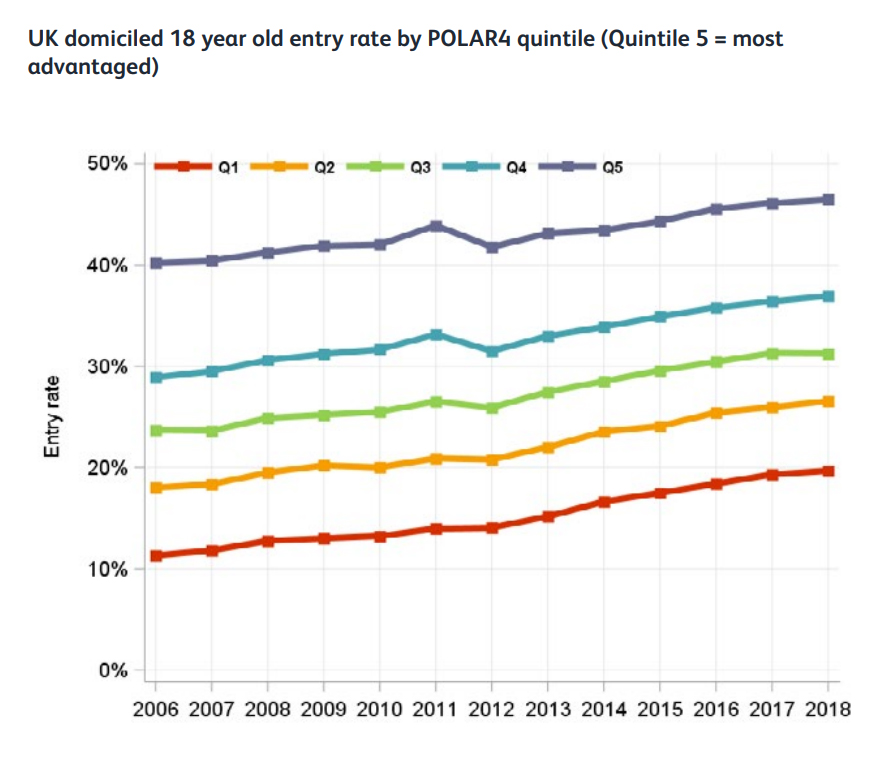

Along with our charity colleagues, we've been campaigning to make sure that university access is as fair as it can be for all young people, as the Augar review nears its completion.

In November we issued a call on the Government to protect funding for widening participation to make sure that the great work and progress that's been made to close the Access Gap doesn't get wasted, and met with the then-Universities Minister Sam Gyimah MP to talk about the importance of protecting widening participation.

The year in feedback

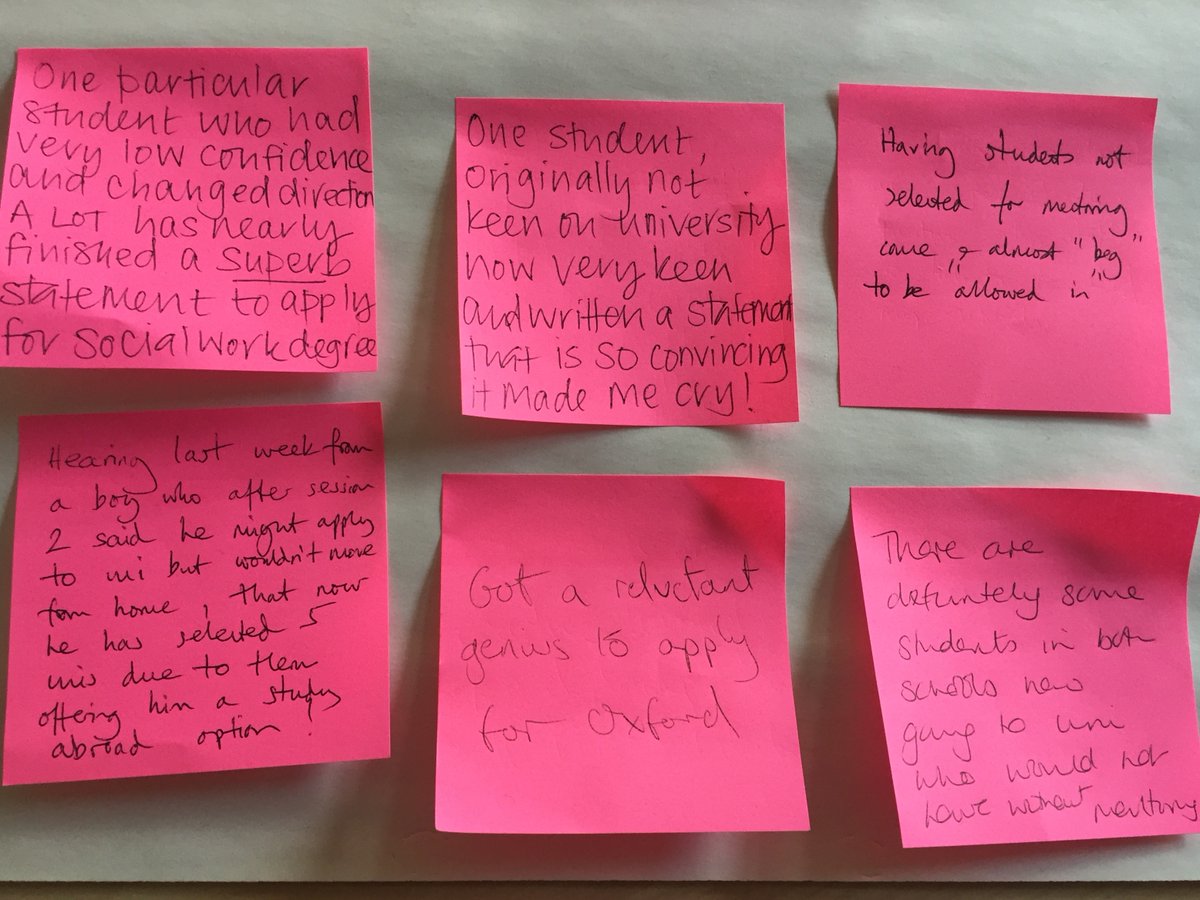

We often get feedback from people we work with. It's always useful to hear from those who matter what they think of what we do - and especially so when it's positive! Here are some of our highlights from the work we've done this year, starting with some reflections from our Progression Specialists when we asked them to share a personal highlight from their year's mentoring.

“We really do feel that you have made a significant difference to the students’ progress and confidence. [Student] was with us just now and you have clearly had a real impact on his future plans. The students you have worked with are very lucky indeed.”

“I would just like to thank you. You’ve done everything you could to help with my personal statement. My teachers love it…God bless you…You are a role model as you selflessly aid people to get into their future careers.”

“It made me think of options that I haven’t thought of before, making me calmer in terms of my university options.”

The year in stats

As well as the wonderful feedback, we're a research-led organisation so whenever we've been out and about we've been busy collecting evidence to help us understand the impact and value of our work, and how it helps to change young people's lives.

There's some real evidence of promise, and as we work through the data we'll share what we find over the coming weeks. But the basic stats about what we achieved last year are pretty impressive on their own:

We delivered more than 60 workshops and training days with teachers from more than 100 schools.

99% of people who attended our Access Champions training days in 2018 reported that they had left with clear ideas about strategies they could implement to improve systems in their school/college.

Our Progression Specialists held over 4600 mentoring sessions with more than 1100 students.

More than a third of students we mentored said they were more likely to go to university after completing their mentoring sessions.

More than 3,400 students worked on their personal statement using OSCAR.

So while there's still much work to do to make sure all young people have fair access to education, we're already making a real, measurable difference to young people's lives.

We'd like to say a huge thank you to everybody who helped make 2018 such a success - we really enjoyed working with you. We have great plans to do even more and even better this year, and we're looking forward to greater success in 2019.