“Britain’s deep social mobility problem, for this generation of young people in particular, is getting worse not better.” – Social Mobility Commission State of the Nation Report 2017.

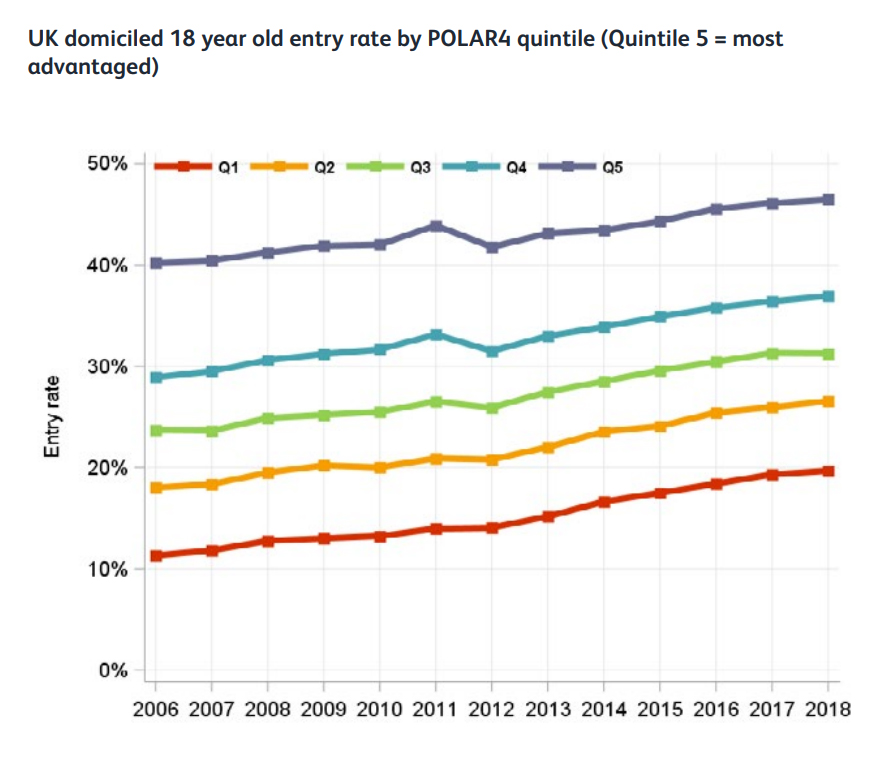

Higher Education (HE) should be a route open to all young people, irrespective of background. But we have a big and persistent social mobility problem in the UK: young people from disadvantaged backgrounds are half as likely to progress to HE as their peers.

Widening Participation funding exists to help close this gap. This funding is vital to the work that we – alongside universities, the Office for Students and others – do to support young people from under-represented groups to progress to, and succeed in, HE. This funding is now in question.

Our request to government

Irrespective of what fee regime the review opts for, we call on the government to protect widening participation funding, while building on momentum around spending it effectively

We urge the government to avoid adding complexity to the higher education funding landscape and to ensure that all students have the information, advice and guidance they need to make good choices in HE

We urge the government to increase the amount of maintenance support available to young people, for instance by restoring maintenance grants, so that university is affordable for everyone

We urge the government not to impose a cap on student numbers

Rationale: We are concerned by reports that the government’s review of post-18 education funding is considering measures which could have a detrimental effect on social mobility.

Specifically:

The current student loan system is progressive as no fees are paid up front and loans are paid back contingent to income. Cutting fees to £6,500 would benefit higher earning graduates the most, as they would pay back less of the cost of their education than they do now. Addressing the cost of living, for example by restoring maintenance grants, would be a better way to encourage more young people from disadvantaged backgrounds to access HE.

Unless protected, a cut in fees to £6,500 could eliminate almost all the widening participation funding designed to close the access gap. This is because universities are currently required to spend a proportion of the fee income they receive if they charge fees above that amount on widening participation activities. Universities have already indicated that if fees are cut, they are unlikely to be able to fund their widening participation programmes. Clear arrangements for funding widening participation activity will be needed to replace this lost fee income.

In his speech on social mobility earlier this year, Secretary of State for Education Damian Hinds reminded us that “universities expect to spend £860 million to improve access and success for disadvantaged students, this is a lot of money and it needs to be spent well.”

We agree. The fact that millions are earmarked for poorer communities and students for whom university has not historically been an option is a seldom talked about good news story for the government. This money is being spent increasingly effectively, with better evaluation, an improved regulatory framework and the forthcoming evidence and impact exchange all adding to our ability to put these funds to good use.

As charities involved in access, we rigorously measure our impact and we know that our programmes are getting thousands of young people into and through HE who would not otherwise have had this opportunity. Now is not the time for government to turn its back on the funding we need to do this.

Irrespective of what fee regime the review opts for, we call on the government to protect widening participation funding, while building on the momentum around spending it effectively.

Differential fees would add another level of complexity to student choices in a HE landscape that is already complicated. Students from poorer backgrounds are less likely to receive the advice and guidance they need to make good choices about their course, and we believe there is a real risk that students from disadvantaged backgrounds could choose courses based purely on price, as opposed to the value they might deliver for them.

We urge the government to avoid adding complexity to the higher education funding landscape and to ensure that all students have the information, advice and guidance they need to make good choices in HE.

The affordability of university is a significant concern for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. The current level of maintenance support is not sufficient to cover students’ living costs and contributions from parents to make up this gap are seldom an option for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

We urge the government to increase the amount of maintenance support available to young people, for instance by restoring maintenance grants, so that university is affordable for everyone.

A cap on the number of people going to university is a regressive measure which would hit disadvantaged students the hardest. These young people are less likely to apply, less likely to get in and less likely to graduate. A cap would also be bad for business and risks hampering our global competitiveness. The global trend is for countries to send more young people to university, not fewer.

We urge the government not to impose a cap on student numbers.